- Home

- H. R. Millar

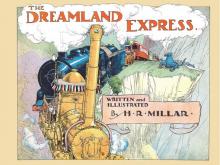

The Dreamland Express

The Dreamland Express Read online

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2015, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published by Oxford University Press, London, in 1927

International Standard Book Number

eISBN-13: 978-0-486-79092-3

www.doverpublications.com

DEAR CHILDREN,

When I was a little boy I wished for a book something like this, but I grew up full-size while I waited for it.

Then, because I thought I should have to wait until I had grown a long white beard and doddled about on sticks, I made the book myself.

So here it is; and I hope you will like it. I have only two wishes now. One, that all this story were true; the other, that you and I might go together on this journey.

What a grand time we should have, to be sure!

H. R. MILLAR.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER THE FIRST

THE TRAIN IN THE WOOD

CHAPTER THE SECOND

SILVER BRIDGES

CHAPTER THE THIRD

NUNCHEL–

CHAPTER THE FOURTH

EBONABAD

CHAPTER THE FIFTH

HEROU

CHAPTER THE SIXTH

ORCHOE

CHAPTER THE SEVENTH THE

TRACK OF THE EQUATORIAL

CHAPTER THE EIGHTH

THE ADVENTURE OF THE ARMOURED GIANT

CHAPTER THE NINTH

THE VALLEY OF MINTED GOLD

CHAPTER THE TENTH

SOTER

CHAPTER THE ELEVENTH

THE PLACE WHERE THE OLD ENGINES GO

CHAPTER THE TWELFTH

THE EDGE OF THE WORLD

CHAPTER THE FIRST

THE TRAIN IN THE WOOD

THE BOYS SAT UP IN BED AND LISTENED

ON a summer evening John, Peter, and George slept peacefully in their beds, while the sun was still shining outside. I don’t want you to run away with the idea that they had been sent to bed. Nothing of the sort!

They had planned an expedition for the next day and wished to start as fresh as possible: that was all.

John, Peter, and George were going to rise with the lark in search of adventure. But when they laid their heads down on their pillows, they hadn’t the faintest idea that an adventure quite different from the one they had planned was very close to them.

But they slept and, I daresay, would have gone on sleeping if they had not been abruptly wakened by a loud whistle. None of your feeble human whistles, nor even a tin whistle; but a deep, full, rich kind of whistle that only a railway engine makes.

The boys sat up in bed and listened. The whistle was repeated. They stared at one another. The whistle came from the opposite direction to their own railway and had, moreover, quite a different note from that made by the engines they knew so well.

THE RAILWAY IN THE WOOD

It was most puzzling. And when the strange whistle sounded again in short, sharp blasts, the boys rose and threw themselves into their clothes.*

“We must look into this!” said John firmly.

As they dashed for the door Peter seized his camera.

I shouldn’t like to set down the time it took them to reach the wood, from which another long whistle came. (It was half a mile away.) You wouldn’t believe me if I did. Anyway, John, Peter, and George soon found themselves in the middle of the wood staring at a brand-new railway which they positively knew was not there a week before.

On the railway stood a giant of an engine dappled with the evening glow; and attached to it was a train of Pullman cars stretching away back into the trees out of sight. There were cars of all kinds, full of excited children who cheered when the boys broke through the bushes.

They were met by a guard, the front guard, a red-haired boy adorned with a guard’s cap and watch-belt which he had found somewhere. He also had a green flag and a whistle, which he fingered ostentatiously.

“Oh, there you are!” he snapped. “Now look alive! we’re late enough already, and it’s about time you got us going.”

A VERY SMART GUARD INDEED

THE VALLEY OF SILVER BRIDGES

“Do you mean we are to drive the engine?” asked John in amazement.

“Certainly,” answered the guard; “that’s what we called you for. Up with you, smartly, now!”

I don’t think John, Peter, and George quite liked being spoken to in that manner, especially when they observed the guard’s spotlessly clean collar and shiny hair. They had come away just anyhow themselves, and, under such circumstances, it is rather—well, isn’t it?

But, as they found later in the adventure, this red-haired person was a very smart guard indeed who knew all there was to know about “guarding.”

Getting into the cab was like climbing up the side of a battleship, and, do you know, I think there must have been some magic about this engine, because, exactly at the moment the boys’ feet touched the footplate, they found that they knew all about it. Quite suddenly. I don’t ask you to believe this straight away, but John walked over to the driver’s seat and said, “She’s a superheated Baltic,” and George answered, “Yes—oil-fired too!” and opened the valves that set the flame humming in the great fire-box.

I don’t think Peter said anything—he was the quiet one; but from what he tells me, he tucked his camera into a corner and gave his attention to the pumps, the dynamo, and all the wonderful oddments on this delightful machine.

Then the red-haired guard whistled.

John pulled over the regulator, and the train slid out of the wood.

I don’t know to this day how many children there were in the train, because the boys never really knew how long it was.

But there is something I can tell you here: that no boys or girls could travel by that train unless they were true believers in magic.

* I have never been able to do this properly myself.

CHAPTER THE SECOND

SILVER BRIDGES

THE train gathered speed steadily. John kept a wary eye on the speed indicator and watched the needle crawl round the dial. Very soon it had reached a hundred miles an hour, and was steadily moving upwards.

The boys guessed from the “feel” of the engine that the train itself must have been very long and heavy; but although they looked back when the train ran swiftly round curves, the last car was never in sight.

I cannot tell you how many cars there were on the train—but I do know there were thirty-one guards! And they were all wanted.

There were sleeping cars galore, dining cars, afternoon tea cars, play cars, a library car, cars without number—but there was not a single school car.*

THE BOOKS NATS THREW OVERBOARD

All the guards were kept busy, as you can well imagine, with such a number of boy and girl passengers—all, that is, except one in charge of the library car. I can’t remember seeing more than two people using it—the librarian, a studious boy with hornrimmed glasses, and another boy (with glasses also and a butterfly net). The two seemed to squabble whenever they met: not for any particular reason that I can think of, but the boy with the net was a naturalist (Nats for short) and just loved learned books, although there was none of that sort in the library car. He had a habit of wandering round the shelves, looking into books, and it was not at all nice for the librarian to hear them described as “Rot!” or “Rubbish!” and see them flung all over the place and even out of the train.

TOYS FROM THE TOY CAR

Whenever this happened a guard was always called to make Nats behave himself, and put the books back in their proper places; otherwise he would have had no place where he could catalogue the beetles and butterflies which he collected whenever the train stopped. He found many other weird

creatures too, as you shall learn later.

The toy car was a dream! There were toys in it which you could not buy in any shop. I have drawn two, but I have forgotten what you do with them; perhaps you can tell. There were three or four “Pets” cars too. No child was allowed to take a pet to bed with him, which I think was just as well. There would have been but little sleep if pets were allowed to run all over the train. Just think of the hullabaloo that swarms of puppies, cats, and white mice can make! And an odd monkey or two would make sleep impossible, nor could one fancy an owl hooting up and down a corridor train all night. So now you understand what the “Pets” cars were for.

EYRIE: CASTLES IN THE AIR

The red-headed guard called them menageries on wheels, which was very unkind of him.

THE VIADUCT IN EYRIE

All this night, while the moon still hung in the sky, the train ran smoothly until an hour before dawn, when it roared out of a tunnel into the Valley of Silver Bridges. It was named so because of the large number of Silver Bridges that crossed it. There were fourteen of them, and it is impossible to imagine where the builders could have got so much silver from.

The thing that amazed John, Peter, and George was that the train crossed all the bridges one after the other, and having done this, raced at top speed over a long viaduct, and left the gorge through another tunnel. At the other end of this tunnel they broke into the light of day again.

If there was one memory that remained with the boys of this night it was the wondrous beauty of the signal lamps they passed.

Soon after the train ran into daylight it climbed steeply and with increasing swiftness: the rails rose in front of them and clung to the sides of some high mountains. Bridges spanned from hill to hill, each higher than the last; up into the clouds and out again the express raced, from pinnacle to pinnacle, over flying arches that seemed much too slender to hold them up. Who built such bridges was a mystery, and the thought of the weight of their mighty engine and train traversing the slender structures that seemed like gossamer stretching from the mountain tops, gave the boys many a thrill.

IN CLOUD-LAND

After passing the last of the pinnacles the train seemed to ride out on a great cloud.

It was then that George suddenly turned to John: “Where’s the track, John? I can’t see it!” he said.

“Nor I,” said John, “but I can feel it.”

It was very mysterious—something you could feel and yet not see. All around were banks of golden clouds, each as big as a world it seemed; and yet the engine rolled and shouldered its way along, as all engines do on solid rails; then it leaned over, and the boys had that curious feeling of being in pulled outward. It told them that the whole train was streaming up and round a spiral through the great clouds.

They travelled for a long time like this, never out of the clouds, until at last the spires of a great city showed clearly ahead of them against a sapphire sky.

The signals had changed, so that John knew they were to stop, and after passing some beautiful palaces built on billowing clouds, he put on the brakes and drew up gently with the great engine standing out on a viaduct, through whose arches, miles below, little clouds crawled.

The guard leaned out of the window. “Eyrie,” he said in his best guard’s voice. “Two days only here!” and he disappeared so abruptly that he seemed to have dropped through the train. The children jumped down and scattered like a flock of birds, all running to see some particular spot that had taken their fancy.

John, Peter, and George were left alone in a silence that was only broken by the simmering of the engine; and when night came, the tired boys got down and slept on a cloudbank under a moon and stars that seemed strangely near.

In the morning every child found itself back in its little bunk in the sleeping cars. I’ve no notion where the thirty-one guards slept, but all of them were as keen as possible; so were the children, and when breakfast was over they rushed off again to see the castle and palaces they had missed the day before, and run up those wonderful steps that looked like stone but felt like down. All went to see the Doorless House, but, of course, you couldn’t go into it however much you wanted to. Out of its hundreds of windows other children’s faces peeped and smiled at them. It seemed so strange, but all our little travellers recognised someone they had known when they were little and whom they thought never to see again. Perhaps some of you have had friends that have gone away for always like that, so maybe that was why there was no door to this house.

THROUCH WIZARD’S TOWN

I wish you had been at Eyrie to see the great flowerfall. It was just like a waterfall, but made of beautiful flowers that tumbled over a cloud and fell whispering into a profound and scented abyss, and was lost to sight in a blue haze of perfume.

Then John, Peter, and George cleaned the engine thoroughly, and put such a polish on everything that the cab sparkled like a jeweller’s window.

As they stood admiring their handiwork a small vision climbed shyly into the cab and stood beside them. It was a girl, with such bright eyes and the glossiest of little curls peeping out of her bonnet—yes, bonnet, for she was dressed just like your own great-grandmother was dressed when she was a girl at school.

The fashion may have been old, but it only served to enhance the charm of this little lady. I don’t know how to describe the wide, filmy muslin dress, and the green silk ribbons, but you can see them all in the picture on page 78—with the sunshade too.

“Good-morning, boys!” she said. “How do you do? and how do you like your new job?”

You know as well as I do what answers John, Peter, and George made.

“And how beautifully shiny you have made it all!” she continued.

The visitor pointed at everything and wanted to know what each thing was for, so you can guess the boys were almost swept off their feet by an avalanche of questions. Just imagine their anxiety, too, over their visitor’s dainty dress, and the positive agony they felt when the swift little fingers nearly touched something that was hot! And most things are hot on an engine!

She fairly revelled in the great furnace, and found the wireless speaking trumpet (did I mention that the engine was quite up-to-date?) a sheer delight; but she jumped when a barbaric Eastern voice suddenly brayed from it in an unknown tongue, and then squealed with joy when John let out a fierce blast of air from the brake.

And the whistle!

The boys wrapped a clean handkerchief round the handle, and she pulled it to her heart’s content, until all the eagles for miles round left their nests in alarm.

The boys explained all these things as well as they could to a novice. It was very difficult work, for, when they started explaining one thing, a swift question from their visitor would switch them on to another.

“What’s this for?” she asked, “and that?—and what a lot of clocks you have. What do you want so many for? Wouldn’t one be enough?” and so on, going from valve to valve, and from gauge to regulator, like a butterfly among flowers.

Then she gave them one of the surprises of their life.

“I remember Father taking me to see the Rocket at Barton,” she said.

THE GRAND CENTRAL - NUNCMEL-

“The Rocket!” cried the three boys together.

“Why,” added Peter, rather feebly, “you are only about twelve!”

“I’m thirteen really,” said the little lady; “but don’t you know, there’s no such thing as time here.

“I remember the first train,” she continued; “the engine was a tiny thing, much—much smaller than this, but it had a—had a longer Spout.”*

Then, before the boys had quite recovered their senses, she turned in sudden glee on Peter, who had been standing with his back to a corner of the cab all this time.

“Ah—h!” she cried, and pointed an accusing finger at the flustered boy, “you can’t hide them! I saw—yes—GUNS!” She opened wide eyes. “Oh, now I know: we are going to face perilous adventures, aren’t we?

Tell me, do you think it will be tigers?—or rhinoceroses?—or perhaps a dragon? What do you think? and won’t it be exciting?”

John, Peter, and George murmured something about “rabbits,” but the little lady would have none of such small fry; she would be satisfied with nothing less than two medium-sized dragons; which the boys finally had to promise.

But, adventures or no, this happy state of things couldn’t go on for ever, and the boys, coming manfully through a pleasing ordeal, found considerable difficulty in parting with a visitor who did not seem at all inclined to go.

They managed it at last—in the politest possible way. It was John who leaned out of the cab and said, “Ging—Oh! I say! guard, will you kindly show this lady to the afternoon tea car? Thanks very much.”

And so the beribboned and muslined visitor was handed down and carefully conducted back to the train.

That evening the guard called the children in again. Time was up, he said. And after that, “Right away!” And once again the mighty engine strained at the couplings, and the train gathered speed down a steep hill into the oncoming night. The boys knew that they had climbed up a tremendous height to Eyrie, and the earth was a long, long way below them; but this headlong drop into solid blackness for hours on end was a sensation to be remembered. They hadn’t the faintest idea where they were going, and the speed dial stood at one thousand three hundred and fifty miles per hour.

It was all the more mysterious because, when starting, John saw that the guard’s watch was not a watch at all, but a flat brass thing something like this: with a sun, moon, and stars engraved on it. He talked to Peter and George about it; they couldn’t understand it at all, but on looking at the clock in the engine cab they found it changed into an exactly similar brass thing.

The Dreamland Express

The Dreamland Express